Archive Director Tom Blanton’s Must-Read Testimony on the Administration’s Efforts to Improve Open Government

This morning the Archive’s Executive Director, Tom Blanton, is testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee for its hearing on “Ensuring an Informed Citizenry: Examining the Administration’s Efforts to Improve Open Government,” which can be viewed here. Below is a copy of Blanton’s “must read” testimony.

Statement of Thomas Blanton

Director, National Security Archive, George Washington University

Before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

Hearing on “Ensuring an Informed Citizenry: Examining the Administration’s Efforts to Improve Open Government”

Dirksen Senate Office Building, Room 226, Washington D.C.

Wednesday, May 6, 2015

Mr. Chairman, distinguished members of the Committee: thank you very much for your invitation to testify today about open government and the Freedom of Information Act. My name is Tom Blanton and I am the director of the independent non-governmental National Security Archive, based at the George Washington University.

At the Archive, we are veterans of more than 50,000 Freedom of Information requests that have changed the way history is written and even how policy is decided. Our White House e-mail lawsuits against every President from Reagan to Obama saved hundreds of millions of messages, and set a standard for digital preservation that the rest of the government has never yet achieved, as we know from the State Department. The Archive has won prizes and recognition ranging from the James Madison Award that Senator Cornyn deservedly received this year from the American Library Association – joining Senator Leahy in excellent company – to the Emmy Award for news and documentary research, to the George Polk Award for “piercing self-serving veils of government secrecy.”

This year we completed our 14th government-wide audit of agency FOIA performance, with more recommendations like the ones this Committee included in the landmark Cornyn-Leahy amendments in 2007 and again last year with the excellent FOIA reform bill this Committee passed unanimously through the Senate. My statement today addresses each of these areas of open government performance, and the lack thereof.

But first, I want to say that it is an honor to be here today on this panel with the general counsel of the Associated Press. Not only was the AP one of the founders of the now-ten-year-old Sunshine Week, the AP consistently ranks among the most systematic and effective users of the Freedom of Information Act. I am especially grateful to the AP for taking on the number-crunching task of making sense of agency annual reports on FOIA, and providing a common-sense analysis that parts ways significantly from the official spin. The White House proudly repeats Justice Department talking points claiming a 91% release rate under FOIA. But the AP headline reads, “US sets new record for denying, censoring government files.” Who is right? The AP is.

The Justice Department number includes only final processed requests. This statistic leaves out nine of the 11 reasons that the government turns down requests so they never reach final processing. Those reasons include claiming “no records,” “fee-related reasons,” and referrals to another agency. Counting those real-world agency responses, the actual release rate across the government comes in at between 50 and 60%.

In the National Security Archive’s experience, most agency claims of “no records” are actually an agency error, deliberate or inadvertent. I say deliberate because the FBI, for example, for years kept a single index to search when a FOIA request came in, even though that index listed only a fraction of the FBI’s records. But the FBI could say with a straight face, we conducted a full search of our central index, and found no records, and the requesters would go away. Only when we called them on their abysmally high rate (65%!) of no-records responses (most agencies were averaging closer to 10%), did the FBI change their process.

I say inadvertent because FOIA officers may not know where the documents are, and most often the requester doesn’t either. This is why dialogue between the agency and the requester is vital, why a negotiating process where the agency explains its records and the requester in return narrows her request, makes the most sense. This is why the Office of Government Information Services is so important, to mediate that dialogue, to bring institutional memory to bear, and to report independently to Congress about what is going on. This is why the original Freedom of Information Act back in 1966 started with the requirement that agencies publish their rules, their manuals, their organization descriptions, their policies, and their released records for inspection and copying. This kind of pro-active disclosure is essential, and our most recent audit showed “most agencies are falling short on mandate for online records.”

I’ll come back to that point, but let me first give you some of the big picture, since you are examining this administration’s overall performance on open government. The tenth anniversary of Sunshine Week this spring prompted some tough questions: are we doing better than when we started that Week 10 years ago, or worse, or holding our own? As with so many multiple-choice questions, the answer is probably “all of the above,” but I would also argue, mostly better – partly cloudy. My daddy of course once shoveled four inches of partly cloudy off the front steps, so we have a ways to go.

I would say for starters that many of the battles are very different today. For instance, our E-FOIA Audit of 2007, looking at the ten years of implementation after Congress passed the E-FOIA in 1996, found that only one of five federal agencies obeyed the law, posting online the required guidance, indexes, filing instructions, and contact information. Our agency-by-agency audit found that the FOIA phone listed on the Web site for one Air Force component rang in the maternity ward on a base hospital!

Now I would say almost all agencies have checked those boxes of the online basic information and the public liaison, not least because this Committee took the initiative with the 2007 FOIA amendments to put into the law the requirements for designated Chief FOIA Officers and FOIA public contacts, as well as reporting requirements, the ombuds office, and other progressive provisions.

The biggest shortcoming today, besides the endemic delays in response and the growing backlogs that the AP has so starkly reported, is that so few federal agencies (67 out of over 165 covered by our latest FOIA Audit) do the routine online posting of released FOIA documents that E-FOIA intended. We released these results for Sunshine Week this year, and I recommend for your browsing the wonderful color-coded chart we published rating the agencies from green to yellow to red, with direct links to each of the online reading rooms, or the site where they should be but aren’t. This was a terrific investigative project by the Archive’s FOIA project director Nate Jones and associate director Lauren Harper. The headline from their work is, nearly 20 years after Congress passed the E-FOIA, only 40% of agencies obey the intent of the law, which was to use the new technologies to put FOIA documents online, and reduce the processing burden on the agencies and on the public.

The fact of endemic delays and growing backlogs makes proactive disclosure even more important. As I’ve argued before, the zero-sum setting of FOIA processing in a real world of limited government budgets means that any new request we file actually slows down the next request anybody else files. Not to mention our own older requests slowing down our new ones, especially if they apply to multiple records systems. The only way out of this resource trap is to ensure that agencies post online whatever they are releasing, with few exceptions for personal privacy requests and the like. When taxpayers are spending money to process FOIA requests, the results should become public, and since agencies rarely count how often a record may be requested, requirements like “must be requested three times or more” just do not make sense.

There should be a presumption of online posting for released records, with narrow exceptions. I have found in many of the classes I teach that if sources are not online, for this younger generation, they simply do not exist. Many examples of agency leadership – posting online the Challenger space shuttle disaster records or the Deep Water Horizon investigation documents, for example – have proven that doing so both reduces the FOIA burden and dramatically informs the public.

Our audit this year found 17 out of 165 agencies that are real E-Stars, which disproves all the agency complaints how it’s just not possible to put their released records online. You can see the detailed listing of agencies in the charts, and there’s no difference in terms of funding or resources or FTEs or any other excuse between the E-Stars and the E-Delinquents – the difference is leadership. And oversight. And outside pressure. And internal will.

The complaint we hear the most against online posting is about the disabilities laws, that making records “508-compliant” is too burdensome and costs too much for agencies actually to populate those mandated online reading rooms. In fact, all government records created nowadays are already 508-compliant, and widely-available tools like Adobe Acrobat automatically handle the task for older records with a few clicks. The E-Stars dealt with the problem easily. Complaining about 508-compliance is an excuse, not a real barrier.

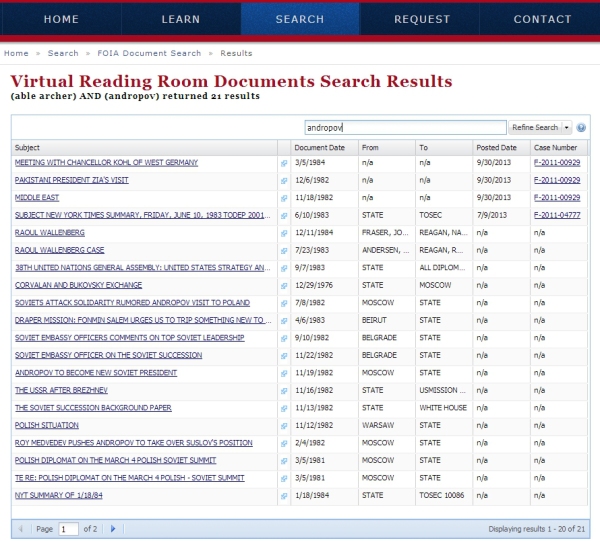

Since the State Department comes in for so much deserved grief on FOIA and records management, I need to point out that here, State’s performance on online posting is one of the very best. As an E-Star, State’s online reading room is robust, easily searchable, and uploaded quarterly with released documents – which allows requesters a useful window of time with a deadline to publish their scoops before everybody gets to see the product. State accomplished this excellent online performance using current dollars, no new appropriations. State’s FOIA personnel deserve our congratulations for this achievement. When Secretary Clinton’s e-mails finally get through the department’s review (which should not take long, since none are classified), State’s online reading room will provide a real public service for reading those e-mails.

Taking the long view on open government also shows that some measures are night and day better than they were ten years ago or even five years ago, and these include some really big ones that we used to have to sue over (and often lose). For example, President Obama early on got rid of retrograde rules that put huge delay in the release of Presidential records, and the Congress last year followed up with deadlines that are now in law. The combination of FOIA pressure and President Obama’s Open Government Directive has opened up Medicare’s extraordinary data on hospital costs and medical procedure pricing – showing dramatic inconsistencies right here in Washington between say George Washington University Hospital and Georgetown Hospital right down the street. My bet is that the recent flattening of health care inflation – with huge positive implications for our budget deficits – comes at least in part from this new transparency.

The Obama administration has made a whole series of historic open government decisions, in addition to the “Day One” declarations on “presumption of disclosure” that this Committee is now trying to put into the statute. Just in the area of national security information that my own organization focuses on, I would point to real breakthroughs like declassifying the nuclear weapons stockpile, and opening the Nuclear Posture Review, and routine release of the intelligence budget, and the declassification of the highly controversial “torture memos” produced by the Office of Legal Counsel at the Justice Department. These were FOIA fights over years or even decades, now resolved on the side of openness and rightfully so.

I would even give the administration credit for rising to the challenge of the Snowden leaks by trying to get out in front of those stories instead of putting its head in the sand. Snowden leaked one of the wiretap court’s secret orders, the one for all of Verizon’s cell phone calls, and in response to the ensuing debate, the Director of National Intelligence and the wiretap court have declassified 40 of the court’s opinions and orders. There’s even a public docket at the wiretap court now. My assessment in the new book After Snowden (coming out this month from Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press) finds that the government has actually declassified more total pages in response to Snowden than have been published by the Snowden media outlets to date.

The most significant progress on open government has been in online access to government data. The consumer product safety complaints database is now public, after years of struggle by consumer groups to open that early warning system. Veterans used to have to file a FOIA request with the Veterans’ Administration to get copies of their service records and health data, and now the VA has created a secure online one-stop access point to make that process so much more efficient, for the government, for the veteran, and for their medical providers. Compared to five years ago, we clearly have access to much more government information than ever before.

And we certainly have more open government levers to use than we did 10 years ago. Sunshine Week deserves some real credit for this, for helping us play both defense and offence. Leading the struggle is the transparency coalition OpenTheGovernment.org (I am proud to be a part of OTG’s steering committee) building consensus and elevating issues. The Open Government Partnership action plan process has proven very useful in helping us pressurize agencies and the White House, and also find and work with the real reformers that do exist in there and want change. The Chief FOI Officers and liaison officers provision put into law by the Cornyn-Leahy amendments in 2007 gives us leverage and even allies at problem agencies and across the government.

I would also single out the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), which though tiny in staff and budget and not nearly commensurate with the Sisyphean task of mediating FOIA conflicts, gives us a shot at changing agency FOIA responses other than just going to court. In comparison to the Mexican and Chilean information commissions, among many other such offices around the world, OGIS simply does not have the clout – yet – to move agency behavior. OGIS does need more funding, more Congressional backing (as in your FOI reform bill, S. 337), and more leverage with agencies, and needs to publish its opinions and build a body of best practice in addition to the FOIA therapy it offers both to officials and requesters.

But at the same time, in the long view, some open government measures are just as bad or just disappointments. For example, when President Obama was a Senator himself, he partnered with Tom Coburn of Oklahoma on legislation meant to put all government contracts on-line, and while there has certainly been progress, we still don’t have subcontractor data up there in usable form. Similarly, the National Declassification Center which we had high hopes for in terms of centralizing the previous daisy chain of infinitely referred decisions instead seems to have just outsourced those decisions back to the agency reviewers. So we’ve had few real gains so far in efficiency or rationality in the national security secrecy system.

Meanwhile, as the Associated Press reported based on the agencies’ own data, Freedom of Information Act backlogs and delays are going in the wrong direction. The average citizen’s experience with FOIA continues to alienate and frustrate. Even though FOIA results keep making headlines, none of those headline-writers would say FOIA is really working. That’s the FOIA paradox – a dysfunctional process that keeps producing records worthy of front-page coverage.

One reason why FOIA does not work is the abuse of the most discretionary exemption in the FOIA, the fifth or “b-5” on deliberative process. This exemption also includes attorney-client privilege, and every lawyer in this room shivers at the idea of infringing on that. Yet, I would point out that the Presidential Records Act dating back to 1978 has eliminated the b-5 exemption as a reason for withholding records 12 years after the President in question leaves office. Through the PRA, we have conducted a 35-year experiment with putting a sunset on the deliberative process exemption, and the facts show us no damage has been done with a 12-year sunset. Yes, some embarrassment, such as the junior White House lawyer who vetted (and rejected) a certain Stephen Breyer for a Supreme Court nomination back in the 1990s. But no new spate of lawsuits. No re-opened litigation. No damage to the public interest. Embarrassment cannot become the basis for restricting open government. In fact, embarrassment makes the argument for opening the records involved.

We were greatly encouraged back in fiscal years 2010 and 2011 when the rate that agencies used the deliberative process exemption to withhold records was actually on a downward trend (from 64,668 invocations down to 56,267). In fact, White House lawyer Steve Croley cited the decline when he appeared at the Sunshine Week event back then at the Newseum, as evidence that the President’s Day One orders on presumption of disclosure were working. We tried to reinforce this White House recognition by quoting one of the former senior staffers of this Committee, John Podesta, who went on to be a senior administration official, when he called b-5 the “withhold it if you want to” exemption.

But neither the White House nor the Justice Department mentions b-5 any more. That’s because in FY 2012 the number jumped to 79,474, and then even higher in FY 2013, to 81,752. This year, the Justice Department does not even give the exact number of b-5 invocations in its summary, only a percentage. But you can do the numbers, and our calculator says “withhold it if you want to” is at an all-time high this year, invoked 82,770 times to withhold records that citizens requested.

This is the exemption that the CIA used – not national security classification – to withhold volume 5 of a 30-year-old internal draft history of the disaster at the Bay of Pigs, even though we pried loose the other 4 volumes, even though there was no sign of the CIA picking up the draft to revise it, even though the now-deceased author of the draft had even filed a FOIA request to get it released. It would “confuse the public,” the CIA claimed, and a divided panel of the D.C. Circuit bought the argument. This is the exemption the Justice Department used to withhold its internal draft history of its Nazi-hunting, and the government’s overall Nazi-coddling, involving governmental cover for hundreds of war criminals. This is the exemption the FBI used to censor most of the 5,000 pages it recently “released” on the use of the Stingray technology to locate individuals’ cell phones. This is the exemption that the administration uses to keep the Office of Legal Counsel final opinions out of the public domain.

This exemption at least needs a sunset, like the Presidential Records Act provides. Personally, I would argue for stronger measures, like the public interest balancing test included in earlier versions of the Senate’s bill last year. Courts are simply not going to infringe on attorney-client privilege, so there is no real danger (but lots of red herrings put out by FOIA reform opponents) from such a balancing test. The threat of court review of the rest of the backroom discussions, plus a sunset, could actually limit the b-5 exemption to those matters that really do need deliberative space for government officials to work out. So we might well see a decline in the invocation of the exemption, the way the bureaucracy responded in those first two years when they thought the Obama White House was serious about a presumption of disclosure. That first impression soon passed, and now we do not even see White House support for the bipartisan legislation that would put the President’s presumption into law. Nowadays, the exemption is the catchall CYA. Here, the House bill (H.R. 653) actually contains better language, not only a 25-year sunset, but also removing b-5 coverage from “records that embody the working law, effective policy, or the final decision of the agency.” This would fulfill one of the original purposes of the FOIA, to prevent any recurrence of secret law.

That brings us to the FOIA reform legislation currently pending. The Archive’s FOIA Project director Nate Jones published an excellent side-by-side analysis of the House and Senate bills on the Unredacted blog on February 4, 2015, so I would direct your attention there and not go into the detail here. See https://nsarchive.wordpress.com/2015/02/04/analysis-of-and-prospects-for-house-and-senate-foia-bills/.

Suffice it to say that both bills would be significant steps forward, and I commend this Committee, Chairman Grassley, Ranking Member Leahy, Senator Cornyn, for bringing S. 337 forward. These bills codify the presumption of openness, requiring records to be released unless there is a foreseeable harm or legal requirements to withhold them. Since this is the ostensible standard set in 2009 by President Obama and then-Attorney General Holder, the administration should be vociferously supporting the legislation. Instead, we have found out from subterranean opposition moves by various agencies, that in fact much of the bureaucracy has not been following the President’s policy, and needs the Congressional mandate to do the right thing.

Both bills require agencies to update their FOIA regulations, a key failure established by the last several FOIA Audits that we have conducted. Half of the agencies have not even updated their regulations to meet the requirements set by the 2007 amendments, so it’s not just the President that agencies are dissing, it’s also the Congress. Both bills reinforce the 2007 amendments mandate that when agencies miss the deadlines, they can’t charge processing fees. Agencies ducked this requirement by calling most of their requests “unusual,” and had Justice Department backing in trying to subvert Congressional intent. Both bills strengthen the Office of Government Information Services, and restrict the b-5 exemption. These are serious reforms that would help requesters, reduce litigation, and make the FOIA process more efficient and rational.

These bills should pass this year, and we will celebrate. What will not happen this year is that the government will preserve its e-mail, or other electronic records. This is an open government disaster in process, in full view, now that Mrs. Clinton’s Presidential candidacy and e-mail practices have put the phrase “Federal Records Act” on the front pages where it is rarely found.

Agencies have been on notice since 1993, when we won the first court rulings that e-mail were records and were covered by the records laws, that printing e-mails to preserve them actually stripped them of value and information such as their links to other e-mail, and that the White House – despite all its claims of Presidential privilege – had to install a computerized archiving system to save its e-mail.

Yet almost 20 years went by before the Office of Management and Budget, with the National Archives and Records Administration, actually directed agencies to save their e-mail electronically. This was after we had to sue again in the George W. Bush administration, when whole days of White House e-mail went missing; and to the Obama administration’s credit, they settled the case, put digital archiving back in place from the first day, and recovered millions of e-mails for posterity.

But the agencies hardly noticed. Both OMB and NARA suffered from two decades of dereliction of duty, until that 2012 directive. Until then, agencies could actually “print and file” as their preservation strategy. I predict you will be hearing agency pleas soon, if they haven’t already started, for new funds for scanning those paper files into digital formats – maybe then, we’ll find out if anybody actually printed and filed anything. I understand nobody can find any printed copies of former Secretary of State Colin Powell’s e-mails from his four years in the State Department, and I wonder how many of Mrs. Clinton’s actually survived in that form.

Even when OMB and NARA finally acted in 2012, agencies got a four-year grace period to start doing what the White House started in 1994. The deadline is December 31, 2016 for all federal agency e-mail records to be managed, preserved, stored electronically. Three years later, in 2019, agencies are supposed to be managing all their records electronically.

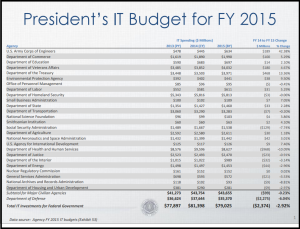

President’s IT Budget for FY2015 shows State Department’s IT budget for FY2014 topped $1.4 billion. Click to enlarge.

So let’s come back to the State Department as our poster child of the day and ask how they’re doing on this deadline. The State Department’s Chief Information Officer, Steven Taylor, has been in office since April 3, 2013, and “is directly responsible for the Information Resource Management (IRM) Bureau’s budget of $750 million, and oversees State’s total IT/knowledge management budget of approximately one billion dollars.” Previously, Taylor served as Acting CIO from August 1, 2012, as the Deputy CIO from June 2011, and was the Program Director before that for the State Messaging and Archival Retrieval Toolset (SMART).

The acronym may have been smart but the implementation was dumb. The recent State Department inspector general’s report found that “employees have not received adequate training or guidance on their responsibilities for using those systems to preserve ‘record emails.’” In 2011, State Department employees only created 61,156 record e-mails out of more than a billion e-mails sent – about 0.006 percent! In 2013, at which point Taylor had failed upwards to the CIO role, only the Lagos Consulate was really saving e-mails, some 4,922 compared to seven from the Office of the Secretary.

Now, the IG report did contain some caveats, such as the statement that those higher-ups like the Secretary actually “maintain separate systems” so perhaps more e-mails were saved. We eagerly await more data on the higher-level systems, which were not in place during Secretary Clinton’s tenure. But I understand that the IG’s office itself could not answer the question of how they saved their own e-mails.

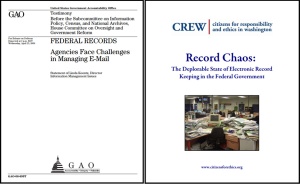

And State is not alone in this preservation crisis. Back in 2008, the OpenTheGovernment.org coalition and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) surveyed the government and could not find a single federal agency policy that mandated an electronic record keeping system agency-wide. The same year the Government Accountability Office produced an indictment of the “print and file” approach, concluding that even the agencies recognize it “is not a viable long-term strategy” and that the system was failing to capture “historic records “for about half the senior officials” surveyed.

So what we have here is a generation of lost e-mail records. From at least the point that the White House started having to save their e-mail electronically, the agencies should have done so as well. But no one tasked them to do so, OMB and NARA were missing in action, and the government opposed our efforts in the courts to spread the precedent government-wide.

Perhaps the greatest irony of Mrs. Clinton’s use of a private server to host her e-mails is that she likely preserved more of her e-mails there than the State Department systems would have done had she exclusively used a state.gov account.

Preparing for this hearing, I read through the State Department’s strategic plan, and other documents on its budget requests to the Congress. Nowhere do I find any provision, any planning, any line item that would address the OMB/NARA directive for managing records electronically. There is a December 2016 deadline, and a billion dollars already going into IT at the Department, but no apparent planning. Maybe it’s just hidden by the b-5 exemption.

I am told that State spent over $100 million on the SMART system. State needs to order and train its employees to start using the system. In the Foreign Affairs Manual (online) you can find pretty straightforward instructions for how to convert existing e-mail into the system, just “click the Convert to Archive button.” After some sustained training and consciousness-raising, the IG should check to see how many converts came over. Obeying the records laws, and the FOIA, should be a core requirement of every job description and performance review.

Finally, I understand that the State Department is now asking the Congress for a so-called “b-3” statute amending the FOIA to exclude “foreign government information” from the reach of the FOIA. This is a terrible idea. Right now, such information earns protection only if it is properly classified, meaning that its release would harm an identifiable national security interest. Even with this limitation, the State Department routinely abuses the designation. For example, last month we posted the censored State Department cable from April 1994 titled “US drops bombshell on the Security Council,” with the passages about the bombshell whited-out on classification grounds, as foreign government and foreign relations information. But we already had the details on the bombshell in the accounts by the British, Czech and New Zealand ambassadors on the Security Council, whose telegrams had all been released by their own governments under their access laws, showing the U.S. pushing for full pull-out of United Nations peacekeepers from Rwanda just one week into the 1994 genocide there. In retrospect, scholars and policymakers – including those ambassadors and the U.S. ambassador who sent the cable, Madeline Albright – all agree that the pull-out was a tragic mistake, that the peacekeepers should have been reinforced instead. Release of this cable would not have damaged U.S. national security in 1994, while the genocide was going on, and certainly does not do so today. In fact, release back then might have saved some lives.

Similarly, the State Department fought all the way to the Supreme Court in the Weatherhead case in 1998 to withhold as classified foreign relations material a British letter on an extradition case, only to have the Court moot the case upon finding that the letter had already been provided to the attorneys for the plaintiffs. No damage to U.S. national security at all.

A “foreign government information” exclusion as a b-3 exemption would effectively import into our laws the lowest common denominator of foreign countries’ secrecy practices. Instead, the standard needs to be “foreseeable harm” to our own national interests, with a “presumption of disclosure.” We can lower our standards so diplomats are more comfortable cozying up to dictators, or keep everyone on notice that ours is an open society, and that’s where we draw our strength and our ability to address and fix problems.

But meanwhile, the Chief FOIA Officer report from State shows they are shifting resources over from FOIA processing to responding to FOIA litigation. To me, this sounds like an endless loop. Slow down the processing and you will certainly get more FOIA lawsuits.

What they need to do is create a SWAT team for records about Mrs. Clinton’s tenure as Secretary. She is running for President, public interest is very high, delay and denial will only escalate the FOIA litigation, and this should be a top priority for the Department. The team needs to roll through the review of the 55,000 pages of Clinton e-mail and get all that public immediately. Then, with some experience from her most direct records, the team can proceed to review and release all her schedules and calendars, senior staff meeting notes, memcons and telcons, for starters. All these records will be the subject of FOIA requests, and probably already are. Proactive disclosure is the only remedy to the State Department’s problems with rising litigation over the Clinton records.

Again, I thank this Committee for its attention to open government, for its support of FOIA reform, and for holding this hearing today. I ask the Committee’s permission to include this statement in the record, and to revise and extend these prepared remarks to include responses to the other witnesses today.

Archive Director Tom Blanton during his first appearance on The Colbert Report in 2010.

Thomas Blanton is the director (since 1992) of the National Security Archive at George Washington University (www.nsarchive.org), winner of the George Polk Award in April 2000 for “piercing self-serving veils of government secrecy, guiding journalists in search for the truth, and informing us all.” He is series editor of the Archive’s Web, CD-DVD, fiche and book publications of over a million pages of previously secret U.S. government documents obtained through the Archive’s more than 50,000 Freedom of Information Act requests. He co-founded the virtual network of international FOI advocates www.freedominfo.org, served as founding co-chair of the public interest coalition OpenTheGovernment.org, and also served on the first steering committee of the international Open Government Partnership. A graduate of Bogalusa (La.) High School and Harvard University, he filed his first FOIA request in 1976 as a weekly newspaper reporter in Minnesota. He won the 2005 Emmy Award for news and documentary research, for the ABC News/Discovery Times Channel documentary on Nixon in China. His books include The Chronology (1987) on the Iran-contra scandal, White House E-Mail (1995) on the landmark lawsuit that saved over 220 million records, and Masterpieces of History (2010) on the collapse of Communism in 1989; his articles have appeared in The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, Slate, Foreign Policy, Diplomatic History and in languages ranging from Romanian to Spanish to Japanese to Finnish (inventors of the world’s first FOI law). The National Security Archive relies for its $3 million annual budget on publication royalties and donations from foundations and individuals; the organization receives no government funding and carries out no government contracts.

Comments are closed.

Reblogged this on sonofbluerobot.